California Farmers: Grow Big or Go Home?

What’s a California Grower to Do?

Editor’s note: This week (June 19, 2017), Leafly launches a four-part series on California cannabis farming by Paul Roberts, author of “The End of Food.” Roberts examines the choices California cannabis growers face as the state enters the legal era: Scale up, build a craft brand, join a cooperative, or go deeper underground. Today: Is scaling up the best move?

When Jai Malloy started working in cannabis a decade ago, as a trimmer on a farm in Northern California’s famed Emerald Triangle, “state of the art” meant a 10,000 square-foot cold-frame greenhouse with manually operated blackout tarps. In a good year, a skilled grower could get three harvests and a total yield of two-and-a-half ounces for every square foot of growing area.

Since then, the state of the art has evolved. So has Jai Malloy. He now co-owns his own brand, Phinest Cannabis, and a parent company, Green Coast Industries, that has become a prime example of the industry’s new business model. This year Green Coast is breaking ground on a $11 million, 100,800 square-foot greenhouse with a full acre of plant canopy—the maximum allowed under the state’s evolving cannabis laws.

Do California growers have to scale up? Or can they survive and thrive at craft level?

Located in Yolo County, a few hours east of the Emerald Triangle, the vast structure will feature fully automated blackout covers, central cooling, CO2 enrichment, and a positive-air pressure system to keep out pollen and other contaminants. Sensors will continually monitor sunlight strength and, when necessary, supplement the solar rays with more than 1,000 high-pressure sodium bulbs. The high-tech setup will allow five-and-a-half crops a year, staggered for continuous harvest, and its total annual per-foot yield will come in at eight ounces, or nearly quadruple that of the old Mendocino operation.

All told, the project is expected to produce around 12 to 15 tons a year, much of which Green Coast will process into a line of edibles, waxes, and other concentrates to be sold their own branded storefronts, beginning with outlets in Sacramento, San Jose, and Los Angeles.

Malloy himself seems almost shocked by how far things have come in a short time. “What we were doing then and what we’re doing now,” says Malloy, pausing. “It’s apples and bowling balls.”

1m Square Feet Under Production

Malloy’s metaphor captures the radical change in the California cannabis sector over the past decade. And it also gets at a question that may determine the winners and losers in the state’s $8 billion cannabis industry: Does size matter?

Cannabis farmer Jai Malloy in his greenhouse in Santa Cruz County. Malloy’s next facility will be a $9 million, 108,000 square foot greenhouse in Yolo County, east of Sacramento. (James Tensuan for Leafly)

Cannabis farmer Jai Malloy in his greenhouse in Santa Cruz County. Malloy’s next facility will be a $9 million, 108,000 square foot greenhouse in Yolo County, east of Sacramento. (James Tensuan for Leafly)

Since 2015, when the California legislature passed a sweeping medical cannabis regulation act, the state’s marijuana farming sector has experienced a period of frenzied growth. That excitement was supercharged when voters passed adult-use legalization last November. Now, as Gov. Jerry Brown and the state legislature labor to turn those laws into on-the-ground regulations, Californians of all stripes have struggled to answer the question: What will—or should—the post-2018 cannabis farming landscape look like? Will only big operators, who invest millions of dollars to scale up, survive in the coming market? Or will there also be room for traditional craft-scale growers?

California’s cannabis market already accounts for 27% of the national total. And that’s before adult-use legalization.

The answer isn’t as simple as you might think. To judge by media coverage, large-scale operations like Green Coast Industrial are the future. Up and down the state, from Yolo and Monterey counties in the north to Desert Hot Springs and Needles in the south, investors are pouring tens of millions of dollars into a fleet of large-scale, high-tech, ultra-efficient cannabis operations engineered to generate very large volumes of super-consistent product.

In Monterey County alone, as much as one million square feet of cannabis production is either planned or already under development. This industrial-scale efficiency, many observers say, will allow the Golden State’s legal cannabis market, which already accounts for 27% of the US total, to more than triple by 2021, to $5.8 billion, according to the latest estimate from Arcview Research.

RELATED STORY LA’s New Proposed Cannabis Regs: Here’s What You Need to Know

RELATED STORY LA’s New Proposed Cannabis Regs: Here’s What You Need to Know

But appearances can be deceiving. California’s cannabis landscape will be heavily influenced by regulation—and, in particular, by the way lawmakers reconcile the state’s 2015 medical cannabis law with more recent, and quite different, adult-use law. For example, the medical cannabis law tends to favor smaller farms and would cap state-licensed growers to no more than one acre of outdoor cultivation or 22,000 square feet of indoor canopy. Under Prop 64, however, that cap would disappear by 2023—which means that what seems huge by today’s standards may someday look small.

California’s 80,000 Cannabis Farms

More to the point, for all the focus on the dozens of mega-grows being developed, nearly all of the cannabis that Californians consume today comes from small farms not so different from the place where Malloy learned his craft. And not just a few: The state Department of Food and Agriculture estimates that California already has between 50,000 to 80,000 cannabis farms. These operations are generally small and low-tech—the antithesis of the modern factory farms. They are also, in many cases, not entirely legal.

A flowering cannabis plant in Jai Malloy’s greenhouse in Santa Cruz County, Calif. (James Tensuan for Leafly)

A flowering cannabis plant in Jai Malloy’s greenhouse in Santa Cruz County, Calif. (James Tensuan for Leafly)

Tucked away in remote places like the Emerald Triangle’s north coast hills, some of them run by second- and third-generation farmers, many of these operations have spent decades producing cannabis for the state’s vast and nebulous medical market—or exporting it into the national illicit market. In 2016, according to Arcview, sales of illicit California cannabis, much of it from small-scale producers, amounted to $5.1 billion, or almost triple the value of the state’s legal production. Of course, many of those small operators want to come out of the shadows—a potential mass migration that will affect both the shape and scale of the state’s cannabis market.

From what we’ve seen in California’s medical market, as well as in the four adult-use states, California’s cannabis farmers will have to choose one of four potential career paths. They can:

- Scale up to industrial-size commodity production

- Build a high-end craft-scale niche brand

- Form or join an agricultural cooperative

- Retire or remain underground and feed the illicit market in non-legal states.

The choices California’s farmer make will reverberate across the national cannabis industry. They will shape everything from wholesale prices to future legalization campaigns.

In the coming week, Leafly will examine these four options that California cannabis farmers will likely need to choose from—and what that’s likely to mean for them, and for the rest of us.

First up: Grow big or go home.

RELATED STORY California Assembly OKs Bill to Prevent Cooperation With Feds on Enforcement

RELATED STORY California Assembly OKs Bill to Prevent Cooperation With Feds on Enforcement

‘Get Big or Get Out’

Back in the 1970s, U.S. Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz famously told America’s struggling grain farmers to “get big or get out”–by which he meant, “Either gain the scale necessary to survive in a low-price, low-margin market, or find some other line of work.”

Today, California cannabis farmers are hearing the same message, in part because the economics of cannabis have undergone the same low-price, low margin transformation. Consider: less than a decade ago, a California indoor grower spent around $300 to produce a pound of cannabis that could be wholesaled for around $4,000. That fat margin reflected the “risk premium” of illicit production and distribution.

Going legal could add $520 to the production cost of each pound of dried flower.

Today margins aren’t nearly so fat. On the cost side, legal producers face a raft of new outlays. There will be taxes and the costs of complying with new state regulations on things like product testing, traceability, and 24-hour security. According the California Bureau of Marijuana Control, going legal could add $520 to the production cost of each pound of “marketable dried-flower equivalent”—with $400 of that coming from testing alone.

Meanwhile, the risk premium has vanished as a flood of legal supply has entered the state’s market. The result is what any economist would expect: Prices have plummeted.

Here are the states with the most and least expensive cannabis in the United States. It’s no accident that the least expensive product sells in legal states. The risk premium has vanished.

America’s Most Expensive Cannabis

| State | Price (1 oz.) | Adult Use Cannabis | Medical Cannabis | Penalty for Possession of 1 oz. Cannabis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maryland | $420 | Illegal | Legal, not yet available | 1 year incarceration |

| Louisiana | $400 | Illegal | Illegal | 6 months incarceration (first offense only) |

| New York | $380 | Illegal | Legal | $100 fine |

| Alabama | $360 | Illegal | Illegal | 1 year incarceration |

| Georgia | $360 | Illegal | Illegal | 1 year incarceration |

Source: Trans High Market Quotations, June 2017

America’s Least Expensive Cannabis

| State | Price (1 oz.) | Adult Use Cannabis | Medical Cannabis | Penalty for Possession of 1 oz. Cannabis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nevada | $200 | Legal, not yet regulated | Legal | $600 fine |

| California | $155 | Legal, not yet regulated | Legal | $100 fine |

| Colorado | $140 | Legal | Legal | None |

| Oregon | $139 | Legal | Legal | None |

| Washington | $110 | Legal | Legal | None |

Source: Leafly.com

Indoor-grown California cannabis now wholesales for around $1,550 a pound. Prices for sun-grown and greenhouse have also fallen. Margins for California’s producers have narrowed considerably, and are likely to get skinnier still, judging by data from Colorado (where wholesale prices are down by half since legalization), and Washington state (by nearly two thirds).

Steady Downward Pressure on Price

Since adult-use legalization in Colorado, “we’ve had to continually adjust price expectations lower and lower and lower,” says Erik Romero, director of data & finance at the Cannabase, a Denver-based B2B “platform” where retailers, cultivators, and processors buy and sell wholesale inventory. Every time growers are sure that “this is the bottom, it can’t go any further down than this—it does,” Romero adds.

Some farmers are counting on greater volume to make up for smaller margins.

Sure, there’s some argument over how much further California wholesale prices will fall, given that the state’s medical market is already so oversaturated. But no one disputes that as the adult-use market matures, cannabis retailers, eager to woo consumers with daily price specials, will press their suppliers for ever-larger discounts.

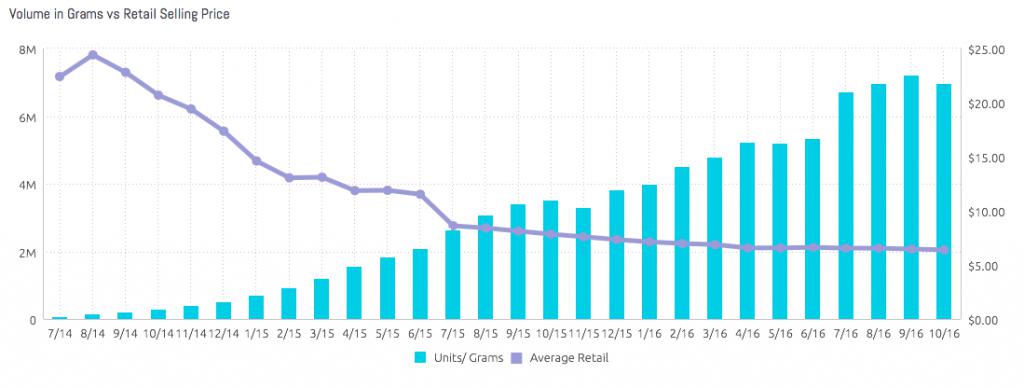

In Washington state, for example, the adult-use retail market opened in July 2014 with $25 grams. The high price was driven by a combination of extreme demand and pinched supply, as most growers hadn’t gotten their state licenses in time to harvest when the market opened. As the state industry matured, prices fell and stabilized. Today a $5 gram is a common bottom-shelf product at most Washington retail stores. BDS Analytics charted the state’s volume rise and price fall like this:

Washington state sales, 2014-2016. As volume increased, price per gram fell. (Chart by BDS Analytics)

Washington state sales, 2014-2016. As volume increased, price per gram fell. (Chart by BDS Analytics)

For cannabis farmers trying to survive this Walmart-like dynamic, the logic of large-scale production is extremely persuasive.

First, by producing cannabis (or anything) in great volumes, you can reduce your per-pound production costs by spreading your expenses (the cost of a greenhouse, say) over a greater number of pounds. These per-pound savings mean you can wholesale each pound at a lower price, which keeps your retailers happy. Second, because you’re turning out such a high volume, you can actually cut your prices even further: even as your profit margin on every pound gets smaller, you’re multiplying that margin over a greater number of pounds. Or as Jai Malloy says of his soon-to-be built farm, “our margins might be smaller than they used to be, but our production will be much, much greater.”

RELATED STORY Tips for Growing Blue Dream Cannabis

RELATED STORY Tips for Growing Blue Dream Cannabis

Scaling Up Requires Big Money

There’s a catch, of course: achieving that sort of scale efficiency takes some serious bank. Malloy’s $9 million venture is actually on the small side; the cost of other mega-grows underway in California top $15 million. But for farmers like Malloy who can assemble the investment, the advantages go beyond simple scale efficiencies.

For starters, there’s a huge technological edge. Having a multimillion dollar budget means you can also afford the sort of high-end agricultural technologies that can generate even greater efficiencies. Leading-edge genetics, automated irrigation, light deprivation, and even robots that mix soil and seedlings: upgrades like these let producers cut costs while optimizing the market value of their cannabis—by, for example, growing plants with the best aesthetics and the highest possible THC content.

In mature markets like Colorado and Washington, hitting that cost-quality sweet spot has been essential, says Romero. Wholesalers and retailers increasingly treat cannabis as a commodity whose price is determined by shelf-readiness—“that is, how well it’s been trimmed, how it looks individually, and how it’s testing THC-wise. That’s pretty much what it boils down to.”

The Rise of SoCal, Where Land Is Cheap

Big budgets can also mean freedom from cannabis’s traditional geographic limits. Gone are the days when Northern California, with its soil and climate advantages, and, especially, its isolated, hide-a-farm terrain, dominated the cannabis trade. With today’s powerful climate control technologies, large-scale growers can move into previously untenable environments such as Southern California’s arid, rural interior, where real estate is cheap. That means growers can spend less of their capital on land and more of it on production enhancements. The result: clusters of industrial-scale cannabis factories in places like Adelanto and Desert Hot Springs (where outside groups are building, among other ventures, a 380,000-square-foot cannabis “business park.”)

The future of large-scale farming may look like the clustered mega-grows in Adelanto and Desert Hot Springs.

From these vast cannabis hubs, operators will be well positioned to feed large volumes of low-cost, biochemically-optimized cannabis to a long-underserved Southern California consumer market. The sales potential of that SoCal market has investors salivating. Cannabis sales in Los Angeles alone, by some accounts, are already topping a billion dollars a year—as much as the entire state of Colorado.

And this may be only the beginning. Because industrial cannabis cultivation is still relatively immature, even the massive grow operations Southern California deserts “are going to appear tiny compared to what is going to happen with legalization,” predicts Tom Adams, editor in chief of Arcview Research. Humans have had decades to perfect the use of industrial scale farming technologies “on everything else that is grown for human consumption,” Adams says, “and that is about to happen to cannabis.”

And yet, it’s just as clear that this large-scale cannabis model won’t be for everyone. Beyond the requirement for huge sums of money, the factory-farm model, as some call it, leaves little room for the quirky variety of California’s legacy cannabis sector—an absence that, as we’ll see, has led to a new opportunity—and a new business model—for a small army of cannabis entrepreneurs.

Background image by James Tensuan

Next in the series: Growing quality cannabis at craft scale.