Satanic Music, Minorities and Sex: The Early Days of Cannabis Prohibition

The post Satanic Music, Minorities and Sex: The Early Days of Cannabis Prohibition appeared first on High Times.

The early days of cannabis prohibition were nothing if not a whirlwind. Although certain states had already started to place restrictions on cannabis, it was nothing compared to the beginning of the nation-wide campaign against the plant. Largely due to the relentlessness of Harry Anslinger, the United States placed a federal ban on cannabis. Today, we have new information and scientific evidence demonstrating the efficacy of cannabis as a medicine and the mostly harmless nature of it as a recreational substance. But we’re still feeling the ramifications of Anslinger’s anti-pot agenda. Here are some highlights from the early days of cannabis prohibition.

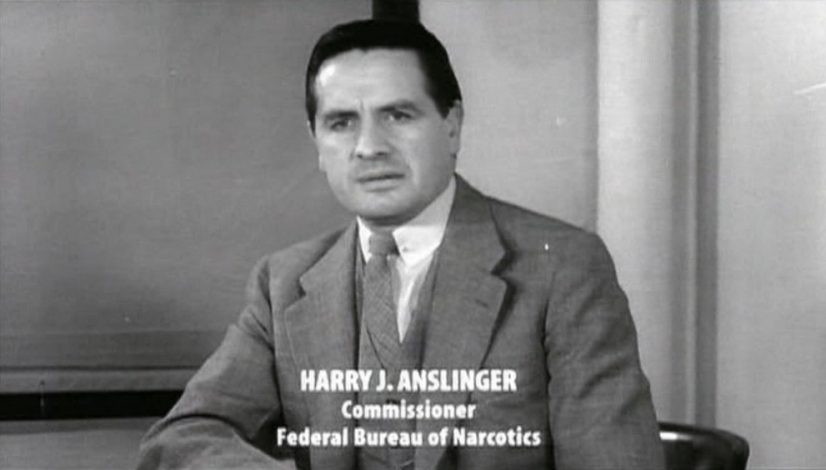

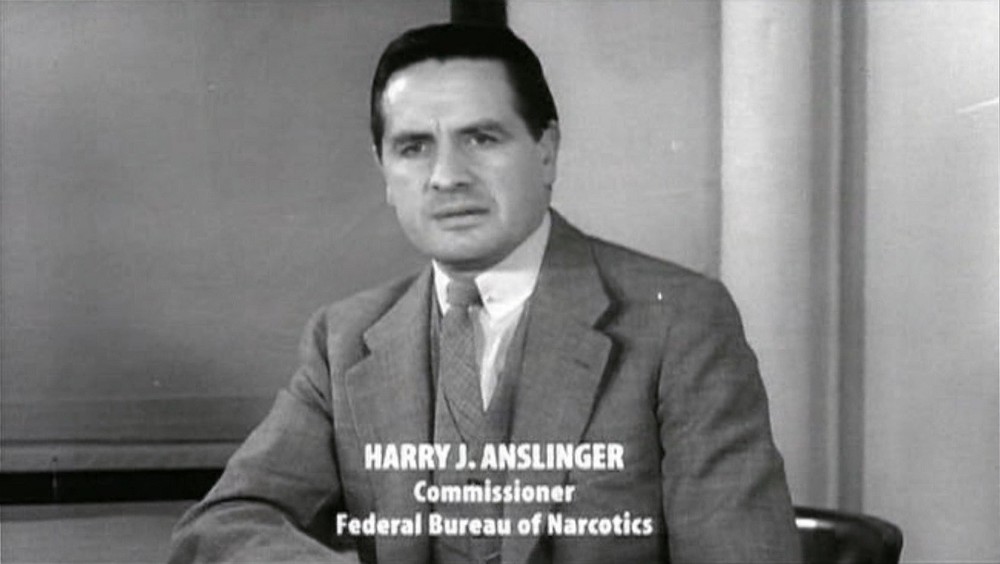

Harry Anslinger

Commonly referred to as the “Father of Cannabis Prohibition,” Harry Anslinger’s official job title was Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. He was the first person to hold that position.

Born in 1892 to immigrant parents, Anslinger began his career as an investigator for the Pennsylvania Railroad. For 10 years, he linked up with the police and military to combat international drug trafficking. Because he primarily worked with the Treasury Department, illegal drug and alcohol trafficking had a purely financial focus—not one based on morals or social issues.

In 1929, Anslinger started working as the assistant commissioner of the Treasury’s Bureau of Prohibition. But then, in 1930, he got the promotion of a lifetime. His wife’s uncle, Andrew W. Mellon, appointed him as the first-ever commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

At this point in the country’s history, cannabis restrictions were already starting to be enacted in a few states. Interestingly enough, when he started his new job, Anslinger had no problem, moral or otherwise, with cannabis. According to sources, he even said that cannabis—then called “Indian Hemp”—wasn’t harmful and didn’t cause users to behave violently.

Then the prohibition of alcohol ended.

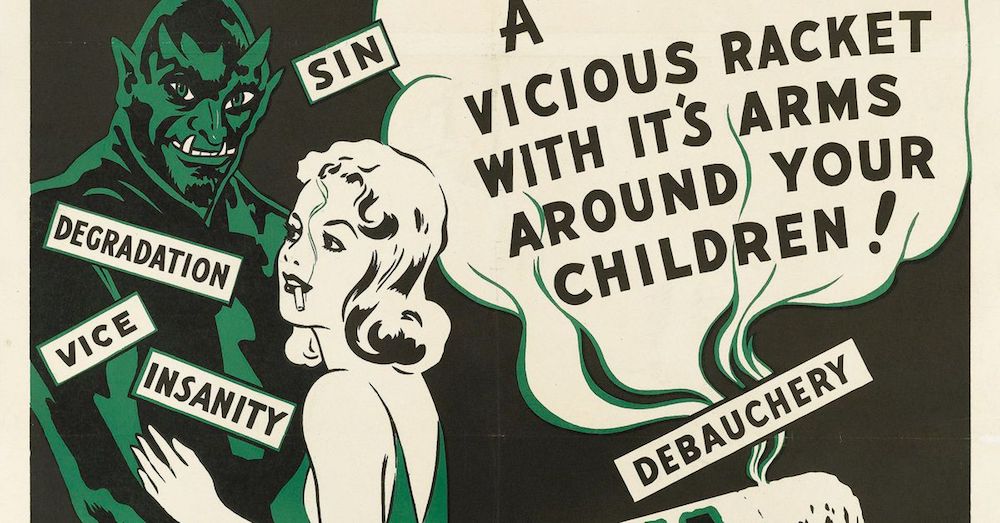

Reefer Madness

Anslinger changed his tune. He began to spread false reports of cannabis-induced madness, violence and crime.

Using the powers of the mass media, he got the American public on his side by releasing what was dubbed “Gore Files.” These consisted of police reports of gruesome crimes supposedly committed by people under the influence of cannabis.

One such crime was the murder of the Licata family in Florida in 1933. Victor Licata, a 20-year-old man, used an ax to kill his parents and three siblings. Although psychiatric evaluation indicated that he was seriously mentally ill, anti-cannabis propagandists, including Anslinger, spread the story that Licata was addicted to cannabis.

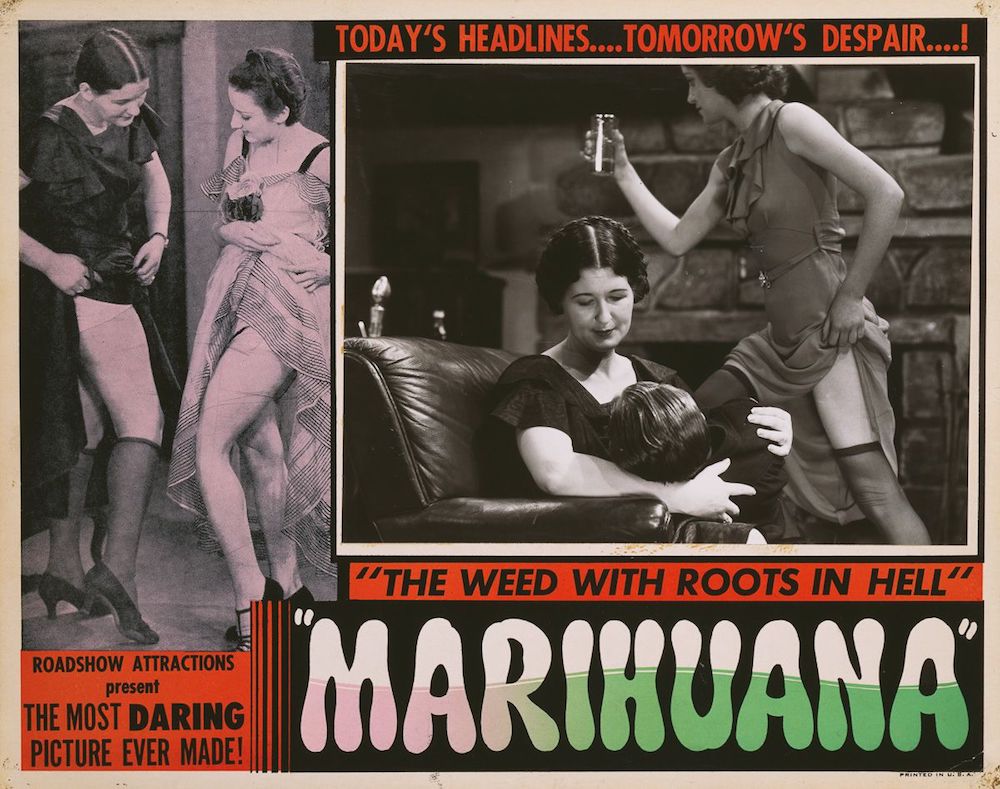

The case was so gory and reached such a wide audience that it even inspired one of the most notorious films released in the United States: the 1936 exploitation film-turned-unintentional-satire Reefer Madness.

Ever the sensationalist, Anslinger kept up the momentum of the idea that cannabis caused insanity.

“Marihuana is a shortcut to the insane asylum,” he said. “Smoke marihuana cigarettes for a month and what was once your brain will be nothing but a storehouse of horrid specters.”

Bad Psychology

The psychosis that cannabis consumption allegedly induced was a running theme in the early days of cannabis prohibition.

During the Congressional hearings for the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, Anslinger submitted a statement titled, “Marihuana—A More Alarming Menace to Society Than All Other Habit-Forming Drugs,” co-written by Dr. Frank R. Gomila and Madeline C. Gomila. Among the many erroneous claims the authors wrote, the assertions that consuming cannabis led to disastrous psychiatric ramifications were plentiful.

From the St. Louis Star-Times of an earlier date, we find the case of a young high school student reported. A case in point is that of a young man, an intelligent high school student, now confined to an institution for the mentally diseased. His experience is entirely the result of acquiring the habit of smoking marihuana cigarettes.

During Anslinger’s testimony before Congress during the Marijuana Tax Act hearings, he also compared cannabis to drugs like opium:

“Here we have a drug that is not like opium,” he said. “Opium has all the good of Dr. Jekyll and all the evil of Mr. Hyde. This drug is entirely the monster Hyde, the harmful effect of which cannot be measured.”

Racism

Anslinger didn’t just use fear-mongering tactics in the early days of cannabis prohibition. In the 1930s, his anti-cannabis propaganda often had an element of racism.

“Colored students at the Univ[ersity] of Minn[esota] partying with (white) female students, smoking [marijuana] and getting their sympathy with stories of racial persecution. Result: pregnancy,” he wrote.

Remember: this was in the United States during the 1930s. Racism was readily accepted in the vast majority of the country. The Jim Crow Laws would continue for another 30 years. Anslinger knew exactly what he was doing.

Furthermore, he famously asserted:

There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, enterainers and others.

And of course, this next inflammatory remark:

Reefer makes darkies think they’re as good as white men.

Anslinger was far from the first to use racism as a means to sway white Americans from the plant. And it wasn’t exclusively against black people.

As early as 1910, the alleged “dangers” of cannabis were publicized in Southern states in an effort to (further) turn the public against Mexican immigrants. Unsurprisingly, these views did not die down. In “Marihuana—A More Alarming Menace to Society Than All Other Habit-Forming Drugs” the authors wrote: “The Mexicans make [cannabis] into cigarettes, which they sell at two for 25 cents, mostly to white high school students.”

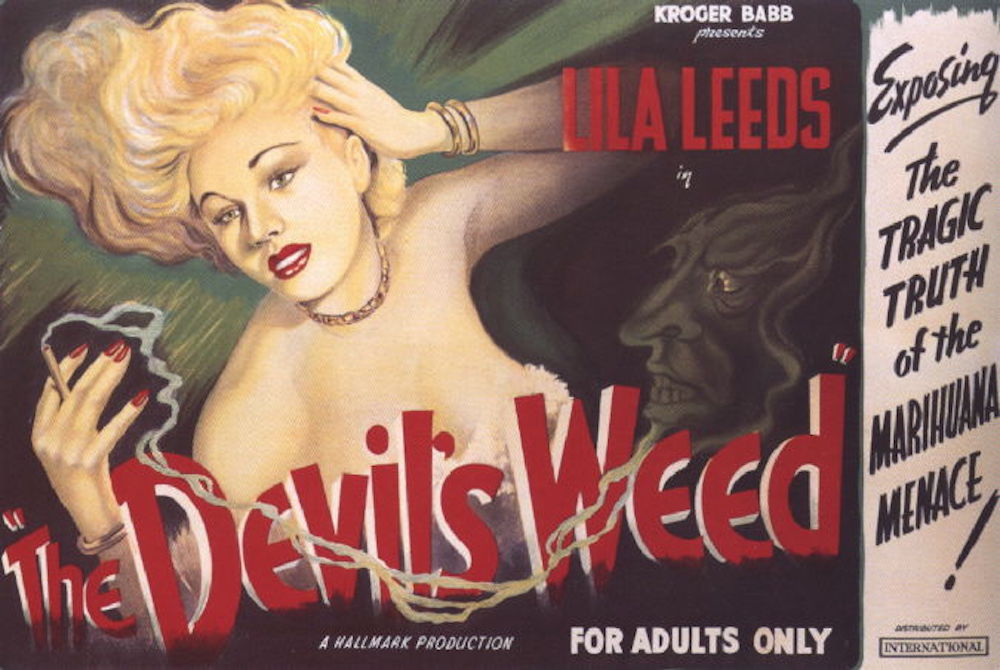

Sex

An additional element of the early days of cannabis prohibition was centered on sex. Specifically, about the sexuality of white women, as well as their supposed vulnerability. This focus didn’t end with Anslinger’s remarks that cannabis consumption inspired white women to seek relationships with black men. And it wasn’t just Anslinger who made statements about the “negative” impact that cannabis had on women.

“Marihuana—A More Alarming Menace to Society Than All Other Habit-Forming Drugs” recounted a story of a young woman who smoked cannabis with her boyfriend and became so intoxicated that they eloped.

Other reports that Anslinger referenced in his testimony during the Marihuana Tax Act Congressional hearings told stories of men—under the influence of cannabis—committing rape. Anslinger himself reported on stories like this in his Gore Files. A notable example:

Two Negros took a girl fourteen years old and kept her for two days under the influence of hemp. Upon recovery she was found to be suffering from syphilis.

The anti-cannabis propaganda during the early days of prohibition reflected this fixation on the idea that cannabis promotes promiscuity. Particularly with films like Reefer Madness and Marihuana, which played into this notion. The message was clear: cannabis was responsible for ruining the virtue of women.

Final Hit: Satanic Music, Minorities and Sex: The Early Days of Cannabis Prohibition

Looking back on the early days of cannabis prohibition is certainly interesting. It can even be mildly entertaining if you are able to view it in a certain light. But while we’re able to look back and marvel at the widely distributed and accepted misinformation and outright lies, it’s important to reflect upon it as well. The ramifications of the early days of cannabis prohibition, and especially of Harry Anslinger’s relentless anti-cannabis crusade, still affect us to this day. Anti-pot activists still attempt to spread falsehoods about the plant. The racial disparity of cannabis arrests still prevails. Even as studies demonstrate that white people consume just as much weed (and sometimes more) as people of color.

As a community, we have a responsibility to push back against these early anti-cannabis efforts. We’ve come so far already. We all must work hard to prevent our society and laws from slipping backward.

The post Satanic Music, Minorities and Sex: The Early Days of Cannabis Prohibition appeared first on High Times.