Recreational marijuana is saving lives in Colorado, study suggests

Published: Oct 16, 2017, 10:28 am • Updated: Oct 16, 2017, 10:45 am

By Christopher Ingraham, The Washington Post

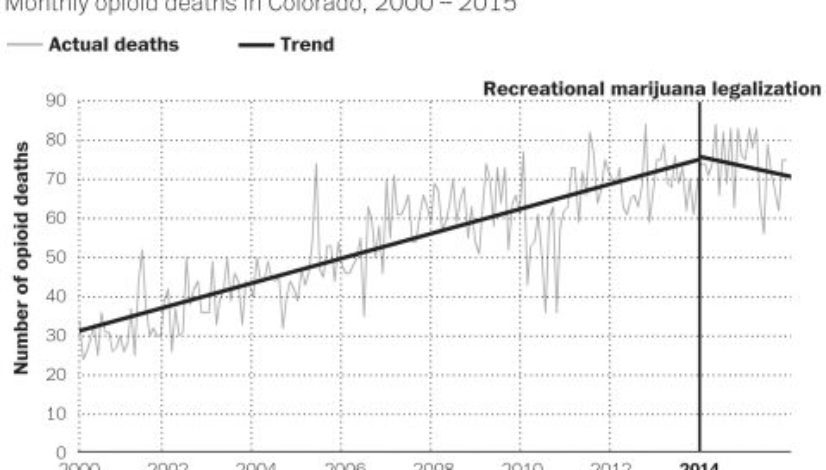

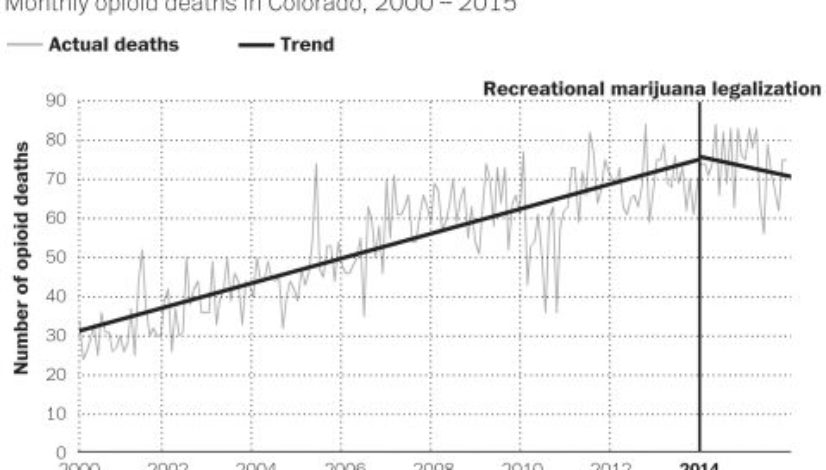

Marijuana legalization in Colorado led to a “reversal” of opiate overdose deaths in that state, according to new research published in the American Journal of Public Health.

“After Colorado’s legalization of recreational cannabis sale and use, opioid-related deaths decreased more than 6% in the following 2 years,” write authors Melvin D. Livingston, Tracey E. Barnett, Chris Delcher and Alexander C. Wagenaar.

The authors stress that their results are preliminary, given that their study encompasses only two years of data after the state’s first recreational marijuana shops opened in 2014.

While numerous studies have shown an association between medical marijuana legalization and opioid overdose deaths, this report is one of the first to look at the impact of recreational marijuana laws on opioid deaths.

Related stories

- Senator calls on Trump to withdraw Marino as drug czar pick in wake of revelations

- How Congress helped drug company lobbyists derail the DEA’s war on opioids

- “No simple solutions”: What the US government should do to combat the opioid epidemic

- Rep. Blumenauer to Congress: Let medical marijuana research help solve opioid crisis

- New Jersey sues painkiller company, calling its methods “evil”

Marijuana is often highly effective at treating the same types of chronic pain that patients are often prescribed opiates for. Given the choice between marijuana and opiates, many patients appear to be opting for the former.

From a public health standpoint, this is a positive development, considering that relative to opiates, marijuana carries essentially zero risk of fatal overdose.

Now, the study in the American Journal of Public Health suggests that similar findings hold true for recreational marijuana legalization. The authors examined trends in monthly opiate overdose fatalities in Colorado before and after the state’s recreational marijuana market opened in 2014. They attempted to isolate the effect of recreational, rather than medical, marijuana by comparing Colorado to Nevada, which allowed medical but not recreational marijuana during that period.

They also attempted to correct for a change in Colorado’s prescription-drug-monitoring program that happened during the study period. That change required all opioid prescribers to register with, but not necessarily use, the program in 2014.

Overall, after controlling for both medical marijuana and the prescription-drug-monitoring change, the study found that after Colorado implemented its recreational marijuana law, opioid deaths fell by 6.5 percent in the following two years.

The authors say policymakers will want to keep a close eye on the numbers in the coming years to see whether the trend continues. They’d also like to see whether their results are replicated in other states that recently approved recreational marijuana, such as Washington and Oregon.

They note, also, that while legal marijuana may reduce opioid deaths it could also be increasing fatalities elsewhere — on Colorado’s roads, for instance.

Still, the study adds more evidence to the body of research suggesting that increasing marijuana availability could help reduce the toll of America’s opiate epidemic, which claims tens of thousands of lives each year.

Related: Rep. Blumenauer to Congress: Let medical marijuana research help solve opioid crisis

Topics: chronic pain, Colorado, opioid epidemic, overdose, recreational, research