Getting Near The Clear: A Guide To Cannabis Distillates

The post Getting Near The Clear: A Guide To Cannabis Distillates appeared first on High Times.

“Civilization begins with distillation.”

Or so said classic American author William Faulkner years ago. The legendary drinker was referring to distilled alcohol, of course, and as his quote notes, distillation has existed since ancient India and Roman Egypt first distilled liquor and water. But in the 21st century, the time-tested tradition of the distillation process has inevitably been modified to become part of cannabis concentrate development—and may represent the coming future of legal pot, especially when it comes to large-scale production.

When the trade name of a cannabis concentrate, of all things, is dubbed “The Clear,” it can have quite a reputation to live up to—and the cannabis concentrate distillation represents just that; the cutting-edge of cannabinoid extraction, where innovation and new ideas continue to push the envelope by developing end-products that provide everything a user desires, from purity to potency.

You’ve likely already tried THC or CBD distillate products, especially if you live in a legal state. Perhaps you’ve purchased distillate in a syringe to be applied to a dab rig, or contained in a vape pen cartridge.

Distillates offer an obvious advantage when it comes to medicinal marijuana applications because of the considerable reduction of impurities in the finished product, as well as the purified oil being vaporized, so the patient isn’t subject to combustible smoke.

Cannabis distillation is intriguing on various levels, as there are still ample opportunities for growth and advancement in this burgeoning sub-industry, ready to blossom into an entirely new approach to producing weed concentrates in a post-legalization world.

Yet, there is also some controversy and unresolved misconceptions about distillates, which will also be addressed.

All of these factors position cannabis distillation as a complex issue with numerous tangential topics, and in order to enhance the discussion, we spoke to a couple of “movers and bakers” in the cannabis distillation industry to provide insight and to counter some of the controversies. These were cultivation and extraction expert David Bonvillain, owner of Elite Cannabis Enterprises and Elite Botanicals in Loveland, Colorado, as well as Adam Lustig, founder of Higher Vision, creators of such powerful products as “Super Oil” (more on that in a later section).

Distilling The Dank

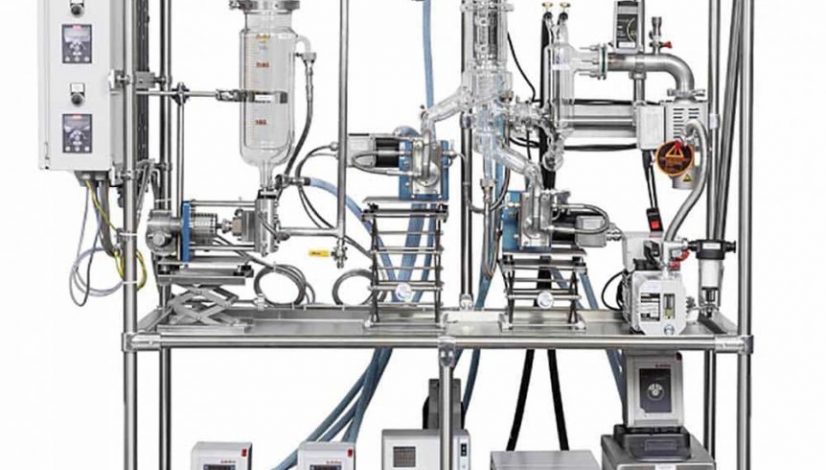

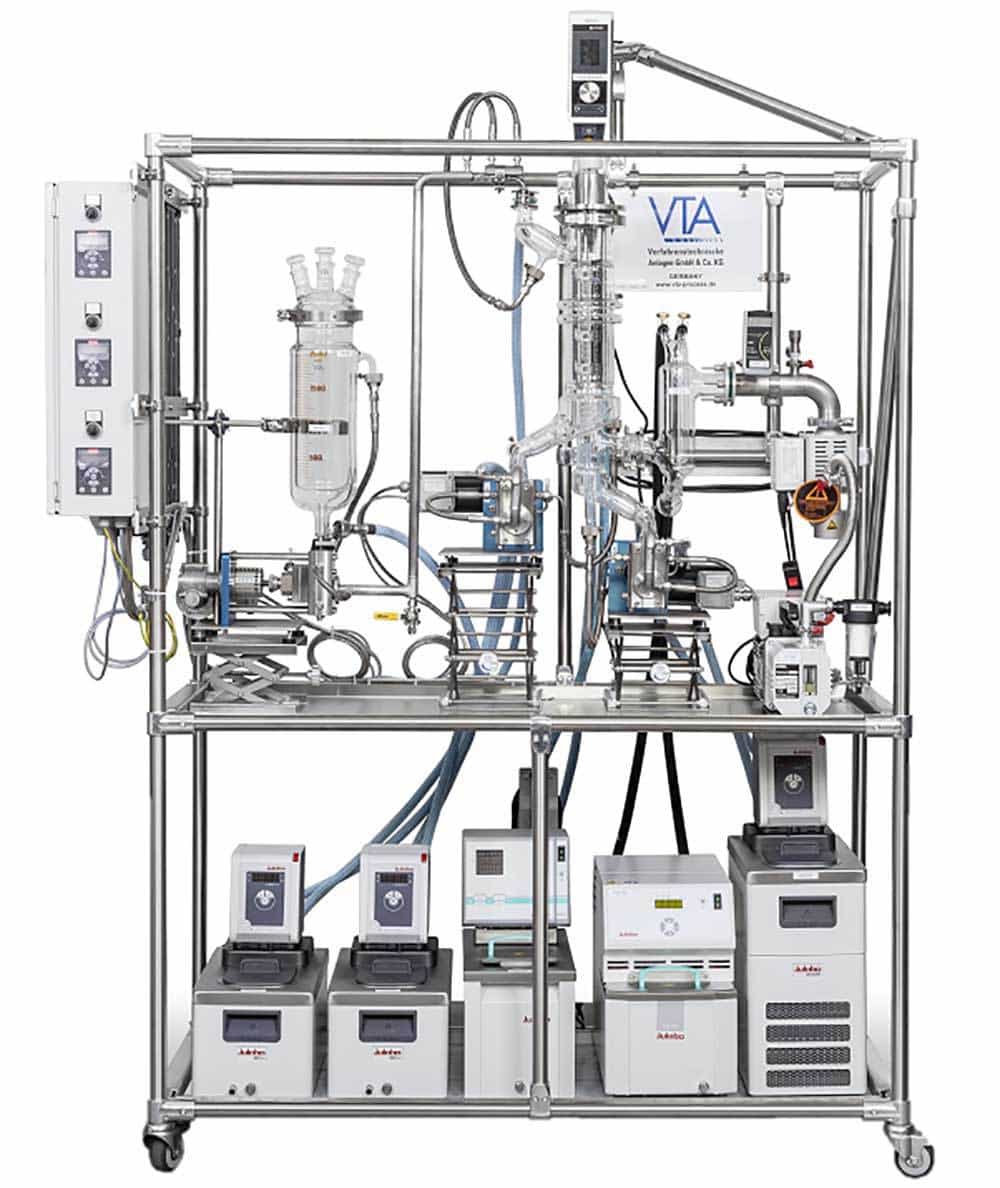

Root Sciences Short Path Distillation System

As noted, distillation has existed since antiquity, but for our purposes, cannabis concentrate distillation is the modern-day process of refining already extracted cannabis material (concentrate oil)—by separating and concentrating three distinct fractions: cannabinoids, the lighter volatiles (terpenoids and flavonoids) and the non-volatiles—the heavier, unwanted materials (pesticides).

In millennial terminology, think of distillate products as being “post-concentrates.”

And it stands to reason that the higher quality extract, the higher quality the finished distillate oil will be.

“One chief advantage to distillates is when you’re looking for that strong, specific cannabinoid formulation for a specific purpose,” Adam Lustig explained.

One example would be a distillate containing the cannabinoid CBD (cannabidiol) for purely medicinal purposes.

Distillation is distinct from more prevalent cannabis concentrate outcomes, like wax and shatter, in which more basic extraction methodology is employed by using thinning agent solvents, like butane, propane or, preferably, via supercritical CO2 for superior taste.

A cannabis “crude oil” butane heated or CO2 concentrate previously containing anywhere from 70 to 85 percent psychoactive THC could be elevated up to a near-perfect 99.85 percent cannabinoid concentration via distillation, as reportedly achieved by Root Science’s distillation equipment.

This process removes all of the undesired elements like ethanol used in the original extraction, as well as plant waxes, fats, chlorophyll and those terminally pesty pesticides.

The finished distillate is lighter yellow in color than pre-distilled crude, with considerable clarity—thus, “The Clear.”

Concentrate distillation occurs not by using the aforementioned solvents but rather by utilizing the differences in the volatility—the boiling points—between various compounds in the crude oil (such as the difference between cannabinoids and terpenes), a technique also known as thermal separation.

Per Skunk Pharm Research, the temperature ranges average 185°-195°C for the lighter volatiles (terpenoids and flavonoids), while cannabinoids are separated at 260°C, with the black non-volatile compounds getting disposed. The high viscosity, or melting point, of the cannabinoids is maintained by keeping the materials warm enough that they flow through the entirety of the distillation components.

This is achieved via technological processes such as molecular distillation, also referred to as “short-path,” which is actually a somewhat overused general term for the physical set-up of a basic glassware, bench-top system—consisting of a boiling flask with a neck attached to a vacuum condenser, enabling the manipulation of molecules which transform the crude oil into vapor collected as distillate in a receiving flask. Such an apparatus can be scaled-up to handle larger liter volumes of cannabis crude.

An example of the processes at work can be found in the proprietary distillation equipment—a “still”—developed by the Wisconsin-based company Pope Scientific. The previously extracted oil makes its first “devolatilization pass”—or “run”—through the Pope still, with vacuum pressure and at lower temperatures, removing any remaining solvents, air, gas, water and even lighter-end terpenes.

The second pass through the still utilizes both stronger vacuum pressure and, as noted previously, higher temperature to pull the cannabinoids away from the heavier, darker, undesired elements, including those despised pesticides.

The first pass is necessary to allow for greater vacuum pressure to achieve more successful distillation of cannabinoids in subsequent runs, by not carrying over unwanted gases or volatiles to the finished distillate. The one drawback to this process is the stripping of the terpenes (see next section).

Belfair, Washington-based company Root Sciences has developed a wiped-film short-path distillation system that enables distilling cannabinoids at a rate of 1500 ml per hour, done at a temperature considerably below their boiling point.

This creates a more “shelf-stable” product that maintains its color and potency after being placed in a sealed container for sales.

The Root distillation system also does not place the feed-zoner under the vacuum, permitting a continuous supply of oil entering into the system, without the interruptions of having to shut off the vacuum, which facilitates the greater mass production of distillate.

After commercial cannabis distilled oil has gone through all of its runs for maximum cannabinoid purity and terpenoids and flavonoids have been added, the distillate can then be formulated and reheated before being injected into a container, cartridge or capsule—depending on the product being manufactured.

Inviting Terps To The Distillate Party

One of the issues that certain cannabis connoisseurs have with some distillate products is their lack of terpenes, which are the oils that provide taste and aroma. There are well over 100 distinct terpenes identified in the cannabis plant, and they actually play a role in creating the desired “entourage effect,” in which various terpenes like myrcene and limonene add to the flower’s physical and mental high.

Terpenes also work in conjunction with and augment the plant’s cannabinoids, such as psychoactive THC and medicinal CBD.

Dave Bonvillain capsulized the dilemma: “As you make things more potent on the cannabinoid side, you’re removing things like terpenoids and flavonoids [cannabis metabolites also contributing to the color, smell and flavor of a strain], the overall ensemble of components that make for the complete cannabis experience a user perspective.”

“You definitely want to maintain the ‘entourage effect’ because when you don’t have all of the terpene activity, you lose some of the firepower,” he continued. “I mean, it’s like when you dab pure THC-A crystals, it’ll make you high as balls, but there’s no ‘pomp and circumstance,’ right? I don’t have a ‘rush’ with it, and I don’t feel lethargic afterwards and ‘racy’ afterwards because there’s no terpenes at all. It’s only the ‘stoned’ part. And suddenly you realize, ‘Hell, I don’t want to smoke it just to get high, I’m already high.’ No, I like the flavor, I like the aroma, I like all of the extra effects that comes with the terpenes!”

Adam Lustig added, “In terms of a full psychoactive effect, you’ll get higher off 70 percent THC with the terpenes than you will off of 90 percent THC with no terpenes.”

Bonvillain’s explained his take on the process of returning a given strain’s flavor and effects to the distillate.

“It depends on the product you want at the end,” he said. “I think the resolution to it now is [to] isolate your terpenoids first. You essentially ‘pull off’ (with vacuum pressure) your terpenoid and flavonoid volatiles, and then you distill everything, so you have you pure cannabinoids. And on the back-end, you can add the terpenoids and flavonoids back into the distillate.”

“It’s not like you’re adding foreign substances, you’re adding back the individual constituents as the product maker sees fit,” Bonvillain added. “Or even, as the plant itself originally did, without all the other crap—unwanted elements like pesticides—while maintaining the original integrity of the plant [in terms of the preserved cannabinoids and terpenes].”

Lustig’s Higher Vision is one of the pioneering companies to add “live terpenes” to distillates.

More commonly referred to as “live resin,” this fresh-frozen concentrate has a much higher terpene content, as much as five times more by weight. Terpene molecules can either be light or heavy—as one might expect, the “light” terpenes create the fruity and floral weed scents, while the “heavy” terpenes are responsible for ganja aromas more pungent and earthy.

Lustig noted, “I can take plain distillate and blend it with five different terpenes and get five different effects from it after consuming it.”

Terpenes from other plants can be added as well, if you’re into strawberry-flavored oil, for example.

When it comes to the importance and use of live terpenes, Bonvillain elaborated: “The reason we smell the weed is that the terpenes are volatile, and they’re coming off the plant all the time, and it’s hard to capture them.”

“As a grower, I want my extract to smell as fresh as when I was growing it; anything less than that frustrates me,” he continued. “We’ve gotten into a lot of techniques trying to preserve that single plant flavor and aroma profile all the way through the process. And fresh frozen plant material [terpenes] that’s run [distilled] shortly after harvest does a better job of that than dry cured plant material, though some prefer that for the more ‘natural’ smell.”

The ‘Dissing’ Of Distillates

Despite the positive developments and growing interest in the world of professional weed, concentrate distillation is still regarded with some derision in particular cannabis circles. A portion of the negativity derives from Internet trolls, no doubt, but is some of the criticism legitimate?

One particular point of contention has experienced oil consumers referring to distillates as the “hot dog of concentrates” on social media platforms like Instagram and Reddit.

The “hot dog” comparison is a reference to distillates being a composite product of allegedly lesser materials, much like when the actual food product for which it’s named is made from lower-grade meats.

However, the critics seem to be missing the point that distillation represents a refinement of the cannabis crude oil and not a downgraded product like an actual hot dog slapped together from meat trimmings.

And as it can so often be with many products in the legal but still fledgling world of weed, it comes down to the quality of the source material—in this case, the cannabis crude oil. Adam Lustig confirmed as much when he noted, “Yeah, some people tend to think distillates are the low-end of the concentrate spectrum, which comes, a lot a times, from distillates being made from low-grade crude [filled with pesticides and other impurities].

Per Motherboard, the distillate producing company Organa, based in Colorado, reports achieving up to a 15 percent yield, which translates into 15 grams of flower producing one gram of distillate. Such a low yield underscores the importance of initiating the process with high-quality flowers and crude oil.

David Bonvillain has obviously given long thought to the subject, and he elaborated on what he’s determined to be the two factors that have driven the “hot dog of concentrates” critique of distillates:

“Until I came to California, I never had seen or heard all of the negative association with distillates, and realized that it was because this isn’t a market like Colorado, where there was this excess amount of extra material on an annual basis, because all the outdoor comes out and people are selling it cheap,” he said. “Or a lot of people are just blasting ‘dirty oil,’ or people have stuff riddled with pesticides, and they turned it into oil, but it’s just sitting in a bucket somewhere.”

“And there was a whole slew of processes where people would take that, and turn it into what becomes very ‘pretty oil’ once it’s fractionally distilled,” Bonvillain added. “Then, they can sell that off, and so distillates got this reputation of, ‘I can turn poop into gold,’ and, that has negative connotations with it.”

One reason that the “hot dog” criticism is levied is due to the presence of pesticides in concentrate and even distillate products.

Bonvillain’s take on this ever-present concern: “Just like with all the pesticide-riddled oil, it’s the responsibility of the distillate providers looking to make quality products to use the best flowers and oil. Because Adam [Lustig] and I both, we grow all our own flowers that are going into our distillates. The reason we make distillates is when I have a product that I want to achieve ultimate clarity, ultimate concentration, that’s just the process I take it through. It’s actually still single-source organically grown whole-plant, or even just flower. We’ve taken ‘beautiful’ looking crude oil that most people would say, ‘What are you doing distilling that?’ But Adam [Lustig] and I, we don’t look at distillation as a way to clean up tainted product—we look at it as a further way to purify high quality product.”

In a pot-perfect world, pesticides present in concentrates and distillates wouldn’t exist because they wouldn’t be used on pot plants in the first place, and ganja growers would solely cultivate with organics, but completely avoiding unwanted impurities is an impossibility—at least in our present climate of cultivation.

David Bonvillain bemoaned the fact that even if cannabis farmers grow completely organic, their outdoor flowers are exposed to wind-swept pesticides used by farmers of other crops that are in close enough proximity to ganja gardens. It’s a larger problem than just cannabis, and one that won’t be easily remedied, unfortunately.

Bonvillain did suggest techniques that can be utilized to combat pesticides, such as changing the pH (acidity) of your distillate solution to further reduce pesticide impurities.

Adam Lustig said flat-out: “The most difficult thing we have found about the distillation process is reducing pesticides and getting them down to zero parts per billion [the ideal weight-to-weight ratio in a cannabis concentration] is something we’ve had to work really hard to get to on a regular bases. This is because distillation, compared to other types of processes, will dramatically intensify the presence of any pesticides whatsoever. And the problem we as a company face is getting quality, clean [crude oil] product on a consistent basis.”

Distillation: The Future Of Concentrates—And Much More

Much like the larger weed industry that surrounds it, concentrate distillation is ripe for improvement and expansion, both in regard to its own equipment and processes, as well as how it will influence and affect cannabis companies in general.

One drawback to short-path concentrate distillation is an overly long “residence time”—the duration the oil is in the still—which, when subjected to high temperatures, can contribute to degradation of the product.

But new tech developments can negate the degradation.

Root Sciences has developed a wiped-film short-path system enabling distilling cannabinoids at a temperature considerably below their boiling point This results in a highly useful “shelf-stable” product that maintains its color and potency once in a sealed container.

When it comes to the previously discussed pesticide problem, David Bonvillain referenced a chromatography machine manufactured by Buchi that he disclosed to us he was soon planning to demo at his Elite Labs in Loveland, Colorado. He had yet to witness its capabilities first-hand, but he was excited enough about its potentialities to label it a “game-changer” in terms of removing pesticides from distillate oil solutions, “100 percent on the back-end.”

Adam Lustig is likewise optimistic regarding future technological developments when it comes to short-path distillation, and he fully expects the continued development of better quality equipment that will enable purer fractional distillate with less runs and superior filtration.

Lustig added: “You’ll see our industry modifying, adapting and fine-tuning the tech used in the botanical extraction industry as a whole. Making things stronger, faster, better.”

One of the exciting aspects to distillate production is the potential to create and innovate.

To that end, Lustig’s aforementioned company Higher Vision has crafted “Super Oil,” a blend of pure THC distillate and those clean, live cannabis terpenes, both derived from the same original source with absolutely no additives. Super Oil’s universality is such that is is fully dabbable, vapeable, edible and entirely topical—Lustig suggests coating a joint with Super Oil before lighting up.

And Higher Vision’s website promises that Super Oil is “only the beginning,” as the company plans to create more groundbreaking concentrate distillate products utilizing their singular approach of “conscious cannabis chemistry,” as Lustig describes the Higher Vision process, defined by the use of organic, environmentally sustainable and health conscious materials.

David Bonvillain anticipates the establishment of larger-scale systems for increased concentrate oil mass production to play a large role in the billion-dollar legal weed industry.

In his own colorful way, Bonvillain offered a summation of the impact he expects distillates—as well as isolates such as THC-free, solely CBD-based oils—will have as the legalization market expands exponentially: “Distillates and isolates represent the future of ancillary cannabis products (edibles, vapes, oils) and broader acceptance and infusion into everyday life.”

“As much as I’d like to be the dirty stoner and say, ‘No, man, it’s just flowers and dabs, there’s where it’s at, man,’—that’s not reality, that’s not how manufacturing products work when it’s done on a massive scale,” he said. “It’ll be concentrate distillation.”

The post Getting Near The Clear: A Guide To Cannabis Distillates appeared first on High Times.